School leaders contribute to learning leaps of vulnerable pupils

In an earlier blog by colleague Yves Larock, the research report ‘How Principals Affect Students and Schools’ was cited to illustrate that school leaders have a significant effect on what and how learning takes place within the school. School leadership wins a nice silver medal and is second only to the personal mastery of the teacher as a determining factor in the learning gains of pupils and young people. The same report also discusses the impact that school leaders have in supporting vulnerable groups and striving for a school culture of equality. Based on the qualitative analysis of case studies in which school leaders promoted equivalence or made these themes debatable, a number of insights are presented. These confirm the view that school leadership matters and can also make a difference for vulnerable pupils.

School leaders who focus on processes and actions that can empower vulnerable groups create the bridge between educational achievement and student wellbeing. This intersection may seem obvious but in reality it is still too often an area of tension where it is necessary to focus on what can be effectively activated in order to focus on equity. Applying such an equity lens can inspire school leaders to think about how they can use their leadership to break down barriers and create opportunities for vulnerable groups within existing structures and processes. The diversity present and the challenges associated with it are made visible and negotiable in order to build a unifying and inclusive classroom and school climate in which all pupils feel valued and challenged.

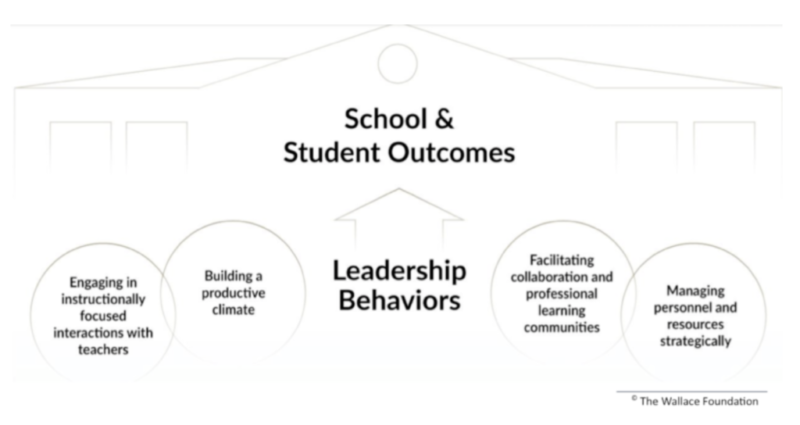

In terms of instruction, an effective school leader can consider how to meet the needs of vulnerable groups. This can be done, for example, by focusing on professionalisation processes that allow teachers to better understand and relate to the challenges faced by students in low socio-economic contexts (Gerhart, Harris and Mixon, 2011) or by promoting inclusiveness through investing in inclusive curricula, co-teaching or flexible pathways. These processes require creativity and perseverance but are often effective when coupled with high instructional expectations and when relying on teachers’ personal mastery. Educationally-oriented interaction of the school leader with the teachers involves feedback, coaching and other ways of strengthening the school and its teaching. Classroom observations, the use of data on learning and teaching and a good dose of people management are possible entrances here.

A focus on equality and embracing diversity essentially means building a school climate that celebrates pluralism and diversity. Diversity is used as a lever. This mindset implies exploring methods in which parent involvement, recovery-oriented work and an open consultation culture, among others, are high on the agenda. By valuing and stimulating partnerships between pupils, parents, teachers and the social fabric, responsibility is taken up and demanded by the various actors (DeMatthews 2018; Larocque 2007). For a school, this means thinking about what processes can be initiated/activated to enable this reciprocity without creating an imbalance. In many schools this thinking is done on a daily basis and it is the school leader who acts as architect and contractor to reconcile the wishes and needs of the different actors.

In the journey ‘Making leaps possible as a school leader’, we support school leaders in their personal development process because we are also convinced of the profit that lies ahead for the school and the pupils. Within the framework of the Great Teaching Toolkit of the Education Endowment Foundation, we also zoom in on effective remediation, learning and motivation strategies that can make a difference for the most vulnerable groups and on which they, as school leaders, can have an impact. Because of the appreciative, inquisitive attitude that we propose within the journey and the way the school leaders get to work with this themselves, new actions can see the light at school level that are effective and lead to a connecting classroom and school climate in which children and young people can come to learning and feel good.

It goes without saying that this is not an exact science, but that the literature and the frameworks provided within the journey can help to see where the possibilities lie.

In this way, we continue to build the schools of the future and the guidance and formation of the greatest capital we still harbour: our children and young people.

Sources: Grissom, J.A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How Principals Affect Students and Schools: A Systematic Synthesis of Two Decades of Research. New York: The Wallace Foundation.